June 30, 2008

By Michael Wohl

The Language Of Film

Film and video programs are efforts at communicating and just like speaking English, tapping out Morse code, or waving semaphores, there is a whole language that can be learned including words, phrases, grammar, punctuation, rules, and common practices. And like any other language, the more thoroughly you master it, the more effectively you can communicate.

While the writer conceives the story, and the director realizes it, it is you, the editor who is the storyteller; given the task of organizing the thoughts and ideas and transmitting the intended message to the audience.

Communication is both an art and a craft. Part inspiration and part perspiration. Effective editing requires both aspects, and while you can't necessarily be taught the art of eloquence, you can study and practice the rules of the language, and hone your craft so you can edit quicker, more efficiently, and communicate more effectively because of it.

Shots As Words

Just as words are the building blocks of a written language, individual shots are the building blocks of the film language. And different shots can be thought of as different parts of speech, serving different purposes and answering different questions.

You are undoubtedly very familiar with the questions: who, what, where, when, why and how. These questions are deeply ingrained in all of our brains because we are constantly asking them-consciously or unconsciously-about everything we see and do in the world. The answers to those questions are precisely the elements our brains use to make sense of the world. And coincidentally, the are the basic components of story.

You probably know someone who tells great stories, perhaps a grandfather or a crazy aunt. You also probably know someone who can't tell a joke to save their life. Did you ever stop to ask what makes one person a great storyteller and someone else a bad one?

Effective storytelling requires doling out the who, what, where, when, why and how answers in equal parts and just in time as the listener is wondering about them. If you dwell too long on one of the questions, without answering the others, the story becomes tiresome and the audience stops listening.

"Three guys walk into a bar. The bar is smoky and dark, there are three bare-bulb lamps dangling, and there's a cigarette burn on one of the tables. The floor is kinda dirty, it's wooden and well worn, and there are about a dozen chairs lined up before the bar...."

Enough where already! Who are the three guys and why are they there? Even a simple joke can be mercilessly ruined by a storyteller who doesn't know this basic rule.

As an editor, your primary job is to control the flow of information, to guide the viewer to pay attention to certain details in a certain order, and to control the point of focus both within the frame and within the story. There are many tools to aid you in this endeavor, but the most basic of these tools are the specific shots you choose. In fact, different types of shots inherently answer each of these questions.

Who

In the film language, the who question is typically answered with the close-up (CU). The primary point of focus in any close-up is the subject's face. This framing typically mimics the experience of what you would see in real life if you were conversing with a person. A close-up is an intimate portrait of someone, more intimate than you would ever get with a stranger. This is part of why fans inherently feel as though they "know" famous actors. (Though the feeling is certainly not mutual!)

Who Are They?: A Close-up gives insight into who a character is.

These shots leave little doubt that one is a no-nonsense sourpuss and the other is a idealistic dreamer.

Close-ups can vary widely based on camera position, lens choice, and other production considerations, but ultimately you can count on such a shot to answer this fundamental question.

If you were to go too long without providing close-ups your audience will lose track of whose story they're following and they will very likely lose interest. This is especially common in complex action scenes where there is so much what and how to convey to move the story forward that it's easy to forget to keep the who present in the viewer's mind. But do so at your own peril. Even the most spectacular battle scene can fall flat if the audience loses track of who it is that's engaged in the fight.

What

If you want to communicate what is going on, you probably need to show a subject performing an activity, and typically, this is conveyed in a medium shot (MS). To clarify, dramatic events are broken down into hundreds of discrete actions that can be described by active verbs (to lift, to threaten, to save, to give, to arrest, and so on.) While sometimes such actions might be subtle and internal enough to be conveyed in a CU, or complex enough to require a sequence of shots, very often the MS provides enough distance from the subject's eyes to move the focus off of their identity, but is still close enough to emphasize what it is they're doing.

What's Going On?: These Medium Shots are perfect for showing a variety of activities.

Where

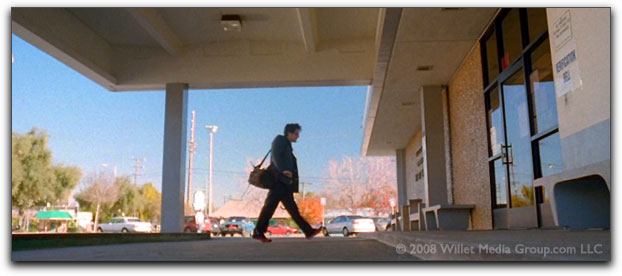

The location of an event is critical. Sometimes this element is deliberately omitted for a while to emphasize suspense or disorientation, but if you go too long without answering this question, the audience will likely grow weary and eventually disengage from your story. The where question is nearly always answered with a Long Shot (LS) though depending on the nature of the scene, sometimes a medium long shot (MLS) or a shot even further away than an LS such as a wide shot (WS) might do the trick.

Where Are We?: Wider Shots clearly show a person in an environment.

The LS shows a subject in an environment. Even if you know the answers to the other questions, watching a scene without having a sense of where it's taking place is literally disorienting. This makes it harder for our brains to process what's going on, and ultimately we start drifting away. Inevitably this leads to the worst possible audience reaction: changing the channel.

One case where this question is frequently omitted is in non-fiction or documentary style shows that contain a lot of interviews. Just because you're dealing with footage of a talking head doesn't mean that the viewer doesn't crave some context to put it in. Incorporating even a brief shot of the room where the interview is taking place, or at least using a wider angle of the interview will show the type of location and provide the answer to this pressing question. (Is it a university office? A jail cell? A baseball diamond? The Roosevelt room in the White House?)

Sometimes, when you don't have the wide shot you need, a clever editor may be able to indicate at least a hint of the "where" using inserts or cutaways to objects or details of the environment, such as a toy on the desk, a diploma on a wall, a bird in a tree nearby, and so on. But one way or another, your audience is dying to know: where does this scene take place?

When

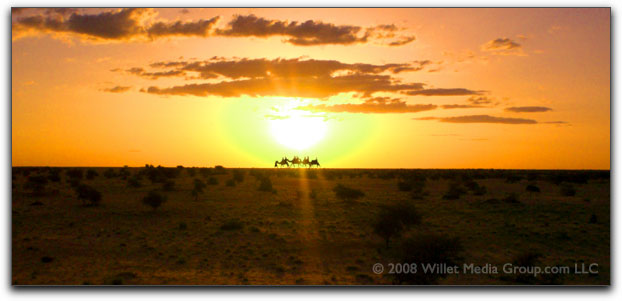

The when question can seem tricky, especially when trying to simplify it to a single shot type. When can mean what period in history, how long before or after an important story event, or it can mean at what point in the overall story arc. The quintessential when shot is the extreme-long shot (ELS or XLS), which illustrates the subject traversing such a vast space that there is a sense of how much time it will take. This could be a car traversing an endless stretch of highway, camels crossing the desert, or a ship in a huge swath of ocean.

A Long Way To Go: The framing here emphasizes how tiny the camel caravan is compared to the huge

desert they must traverse. Adding to the travelers' burden is the further information that the sun is setting

and they're nowhere near any destination.

The idea here is of a where shot so vast that the connection between space and time becomes apparent and it answers the when instead. I know it's very Einsteinian, but trust me, it works. This can be a great shot to help indicate not only the scope of the task at hand, but also to symbolically indicate where in the overall story arc your characters are.

Of course the when question can be answered in different ways too. Sometimes a CU of a particular object, such as futuristic computer panel, or an antiquated telephone can signal the time period, or even the most obvious and explicit of all: a shot of a clock.

Tick Tock: Of course this shot would only be useful if the time of day is relevant to the story,

or if you repeat the shot later to illustrate the time that has passed between the two shots.

Why

This question points to the internal decision making of your subject, and when you want to delve into someone's thoughts, the classic shot to use is an extreme close-up (ECU or XCU or sometimes BCU for big close-up).

What's He Thinking?: ECUs like this one get the viewer wondering what the subject is thinking.

The decision making going on in there can serve as motivation for the action he takes next.

It's interesting that while a close-up gives the viewer the sense that they are in an intimate relationship with the subject, when you get even closer, it's like moving right inside the subject's head. The audience goes from relating to the subject as other to identifying with the subject his or herself.

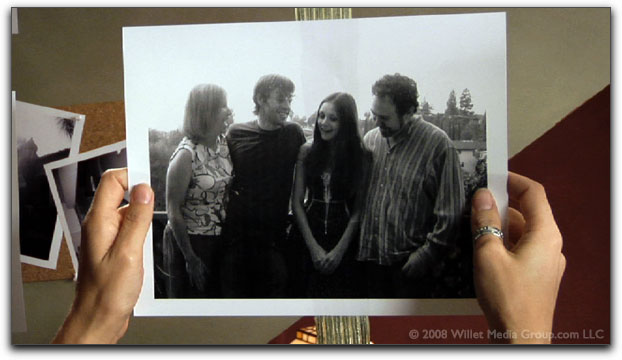

Some why questions may require a more complex approach, using a sequence of shots to explain a bit of backstory or perhaps a close-up on an object or detail that carries emotional significance in the context of the story.

Memories Inspire: In this show, the young photographer reminisces about her once happy family.

This serves as motivation for the action she takes in the following scene.

This is also a case where the magic of juxtaposing two shots can suggest cause and effect. For example, if you constructed a sequence so that a shot of a woman slamming a door preceded a shot of a man signing divorce paperwork, it would imply that the wife's exit prompted the husband to finally go through with the divorce. However, you could tell a very different story by simply rearranging the two shots so the paper is signed before the woman leaves; suggesting that the husband's decision to sign provoked the wife to leave.

How

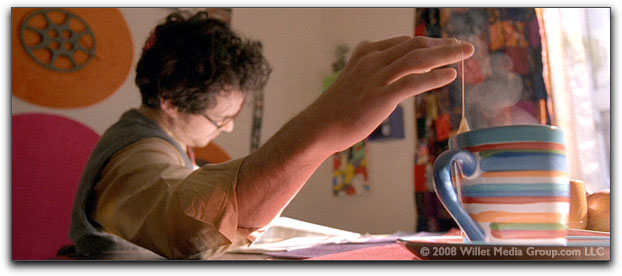

While the why is usually a very internal aspect of the story requiring suggestive shots and editing techniques, the how is just the opposite. This question is very external and is usually answered using either medium close-ups (MCU) of a subject performing a physical action (opening a door, lifting a manhole cover, packing a suitcase, etc.) or a series of CUs or ECUs of specific actions (pulling a trigger, snapping a latch closed, operating a piece of machinery, etc.)

A Very Particular Procedure: The MCU is a perfect shot to show just how meticulously the photographer

likes his tea prepared. This particular example does double duty; since the teacup in the foreground

is like a built-in Close-up of the action itself.

The MCU has a fundamentally different tone than a CU does. It may seem subtle when just comparing the two shots objectively, but in context, a CU is far more intimate and subjective, while an MCU retains enough distance from the subject to maintain a disengaged perspective.

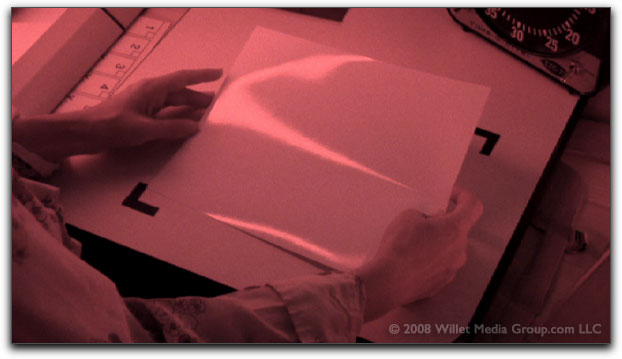

A Chemical Process: In this darkroom sequence, the process of printing photographs is detailed

in a series of close-ups on the physical steps required.

With Whom

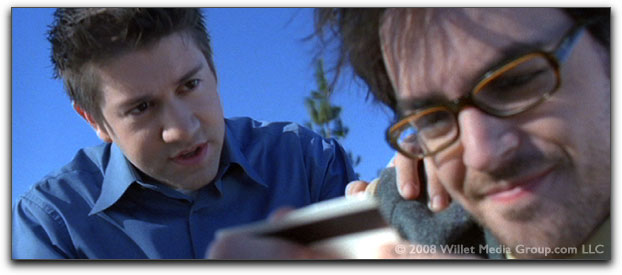

There's one more question that you must answer to satisfy your audience's unconscious need to make sense of the information you are communicating. Whenever you have a scenario with multiple subjects, their relative proximity, posture, and the power dynamic between them is an essential story element. With two people, this information is, by definition, contained in a 2-shot.

Best Buds: 2-shots can vary widely, from the standard over the shoulder (shown first) to a variety

of other arrangements that convey the subtle but critical relationship dynamics that are fundamental

to making sense of the story you are telling.

Naturally, scenes containing more than two subjects will require other, wider shots to illustrate the relative dynamics of all subjects.

Reflected Beauty: This careful blocking allows for all of the important characters to be visible in the same shot.

In the shot below, this group shot of all seven women serves as a set-up, and from here on out in the scene,

the shots are limited to 2-shots and 3-shots.

Often you can deal with one pair of subjects at a time, or group subjects into "factions" creating a "2-shot" where the two subjects each comprise multiple elements.

Us Against Them: These two matching angles treat the pairs of characters as single subjects.

Putting it all Together

Remember it's not just about including all of these different shot types in your sequence, but about anticipating which questions your audience will be wondering and answering them just before they bubble up to the viewer's conscious mind. By the time they're actively wondering, "Wait, how did he do that?" or "What happened to that other guy?" you've already lost them.

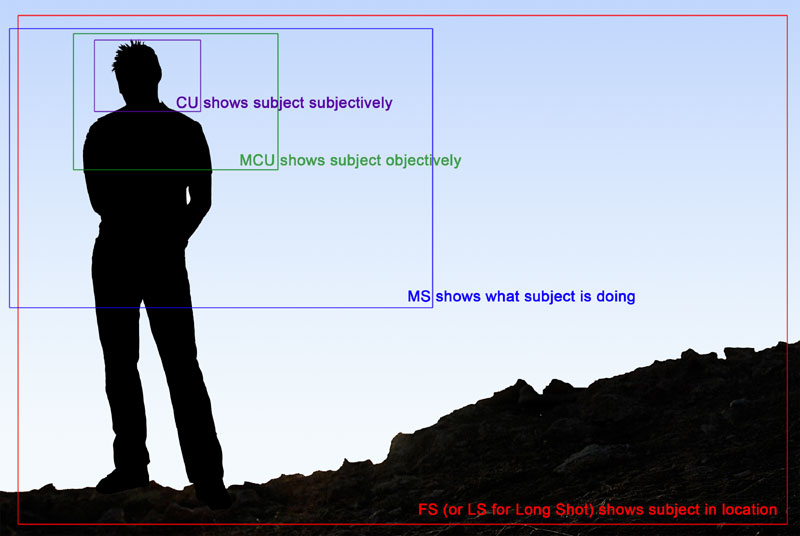

Understanding Shot Sizes

While nothing terrible will happen if you make up your own names for things, it can be helpful to use a standardized terminology for basic shot sizing. The following graphic described the most common framings for a single human subject.

The Full Shot (FS or LS) contains the whole human body. It's considered bad framing to cut off someone's feet. The position and stature of someone's feet communicates a lot of information. (Are they standing firm? Teetering on one side? Shuffling?) Simultaneously, this shot identifies where the subject is located.

The Medium Shot (MS) should comfortably include the pelvis, but not the knees. A lot about posture and physical movement (like walking or dancing) can be determined from the pelvis. Cutting a shot off at the waist is an awkward middle ground between an MS and an MCU; we're further away, so facial expression is harder to see, but without that essential pelvic movement, there's no additional value. Because of this, the MS is typically used to show what someone is doing.

The Medium Close-up (MCU) includes the whole upper carriage like a traditional bust. The way someone holds their shoulders and back conveys a lot of information about their character. An MCU is far enough away to give the subject a respectable amount of space, but close enough to see their face.

The Close-up (CU) should be significantly tighter than the MCU, typically including the collar, but not much of the shoulders. The emphasis here should be on the facial expression, not on body movement. Because the CU is all about the subject's face, it encapsulates their identify, which is why it's the perfect shot to answer who.

The Extreme Close-up (ECU or XCU) [not pictured] could be a very tight framing around a character's eyes, mouth, or some other individual detail. As described above, generally the ECU is a way to get "inside the character's head." This is just as true for interviwees as it is for superheros or ingénues.

Expanding Your Vocabulary

As you increase your cinematic vocabulary, you learn to recognize how different shots answer different questions. And there are more than just those six basic questions but that's where it all starts. You can also think about how certain shots can be used for different purposes. For example, certain shots can serve as Establishing shots, Reaction shots, Inserts, Cutaways, POVs, and so on.

Establishing Shots are used to identify a location and have traditionally been used to introduce a scene. While most commonly they are Wide Shots or Long Shots, sometimes a small familiar detail can serve as an establishing shot. For example, if you cut to a new scene, and begin on a CU of a blinking "Code Blue" light, you quickly inform the audience that you're in a hospital.

Feeling Friendly: The scene that follows this shot all takes place inside the hotel.

We never need to see this outside shot again unless we return here later in the show.

Reaction shots are usually just close-ups of a specific performance showing a subject's reaction to a particular event. Often a reaction shot can be stolen from a different take, or even a different scene. There are many stories of an editor finding a few seconds of footage of an actor with his guard down after the director called cut, and using that clip as a reaction somewhere else in the scene.

What's fascinating about a reaction shot is that it only takes its meaning from the shot that precedes it. The same reaction shot can generate entirely different emotions in the audience depending on what it is that is being reacted to. Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov famously explored this concept in the early 20th century.

Inserts and Cutaways, are invaluable to an editor trying to cut around problems in a scene, or trying to cut some time out of a sequence. Inserts are CUs of objects that have already been seen within a scene, such as a wine bottle or a gun. Cutaways are similar, but the subject of a cutaway is something that has not been seen in any of the other shots. For example, in a scene set in a park, you might cut away to a shot of dogs frolicking, even though we've never seen the dogs before. In another location a cutaway might be a clock on a wall, or other diners in a restaurant.

Have a Cupcake: An insert of the camera-case lunchbox is need to emphasize how extreme a photography

geek this character is. The action of picking up the cupcake provides the perfect opportunity to cut to it.

Note also, that the angle on the insert is the POV of the character.

Inserts are usually pretty limited as to where you can use them: If the subject picks up the wine bottle in the wide shot, that's the only time you can use the insert of the bottle being lifted in CU. On the other hand, cutaways can be used almost anywhere you need to escape from the main action. Of course, the more craftily and elegantly you work the cutaway into the scene, the smoother and less distracting it will be. So, for example, if there was a moment where an actor looked off screen, that might be a perfect time to cut to those frolicking dogs; thereby creating the impression that it was a point-of-view shot (POV).

There are many other shot types and uses you will learn as you gain more experience. And just like learning any other language, the more expansive your vocabulary, the more precisely (and more eloquently) you will be able to communicate. Don't forget also that shots are dynamic and change, a single shot can transform from one type to another through a camera move or through blocking.

Using Verbs

If you think of shots as nouns, you can think of edit points as verbs. Every time you move from one shot to another, you have a variety of choices about how to connect the two elements. You can choose a continuity cut, where the time and action remains continuous across the two shots; you can employ a jump cut,, where time or space is deliberately mismatched; you may make a scene cut, where you transition from one location or event to another; you can use a cross dissolve to simulate time passage, or perhaps a transition from one mental state to another, and so on.

Remember that ultimately your goal is to communicate a story by controlling the viewer's point of focus. Every time you must end one shot and begin another, you create an opportunity for your audience to disengage, so great care must be made in maintaining focus across those transitions.

Rules of Grammar

I know you may think I'm taking this "film as language" metaphor a little too far, but the truth is, it's not a metaphor. It literally is a language, albeit, not a literal one. It's a visual language (and don't think that all the audio elements that go into constructing a sequence aren't just as important, but that's another article entirely).

Just like increasing your vocabulary helps you communicate more effectively, so does learning the common rules of grammar. Most of these rules are intended to hide the artifice of filmmaking so your audience isn't distracted by every cut, or off wondering about how the film was made instead of just getting immersed in the story being told. Now don't worry, just like all rules, sometimes they only exist to be broken, but a broken rule only has value by standing out while you follow them the rest of the time.

Every Shot Must Provide New Information

Perhaps the most fundamental rule of editing is that you should only cut when you absolutely must. The only reason you should cut at all is when moving the story forward requires information not present in the current shot. For example, if you're watching an MCU of a cop who pulls a gun out of his holster, and you can't see the gun in that MCU, you would need to cut to a shot showing that critical story element. If you were on an MS in the first place instead of the MCU, you might not need to cut at all to see the action. However to know whether the cop is frightened or furious or making a joke, you very well might need to cut to a CU.

If instead, you had a single shot that started out on his face, then tilted down to show the gun, then back up to see his reaction, you very well might not need to cut at all, at least until you wanted to see who or what he's pointing that gun at.

Cut on Action

Because every cut is an opportunity for your audience to stop thinking about your story and start wondering what they're going to have for dinner, or where they parked their car, or whether or not they have to use the bathroom, or a hundred other possible distractions, you need to do everything you can to keep them watching across that edit point.

One of the best ways to do this is by using action within the frame to motivate and to hide the edit itself. The action within the frame can be very subtle; if a person simply moves his eyes and looks a different direction, that might be a perfect frame to make your cut, provided that the other side of the edit reveals what it is he just looked at.

Follow the Eyeline: In this scene, the sound of a car crash prompts the character to suddenly look up,

providing a perfect cut point for his POV of the fender-bender below. Note that this also an example of a

cutaway; the fender-bender is in the environment, but was never seen in any prior shot.

Experienced editors are constantly making tiny mental notes of every such action in the footage they have to work with. Head turns, hand movements, eye glances, these are an editor's saving graces, because they provide a reason for the viewer to keep watching after the cut is made. Be sure to make a note of them!

The best scenario of all is where you have continuity of action across the edit point. For example, if you have someone lifting a coffee mug in an LS, and you have an MCU that shows the exact same movement, you can begin the movement in one shot and finish the movement on the other side of the cut.

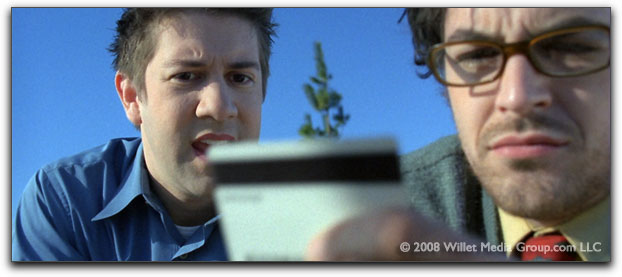

Passing the Buck: One character passes his driver's license to the other, allowing us to cut on the

movement of the ID card to the reverse needed to show the next story beat.

Tying Things Up: In this example, the action of tying the scarf provides ample opportunity to cut back

and forth between these matching OTS shots.

Cutting on action is a crucial and fundamental concept. The idea is to keep the viewer's attention, so if they're watching the movement within the frame and that same movement continues on the other side of the cut, they won't notice the edit-even though the perspective has changed and even though the two shots may have been shot on different days, the continuity of action will make your edit seem perfectly fluid, in fact it will make it invisible.

If the speed of the action is different in the two shots, this makes your job a bit harder, and you may need to experiment with rolling the edit to different points in the action to find the place where the edit feels the most fluid.

What is least desirable is to make the cut before or after the entire action takes place; as that undermines the whole point of cutting on the action itself. If the speeds are so different that this is your only choice, you may be better off looking for an entirely different action to cut on.

Split Edits Whenever Possible

Another way you can effectively hide your edit points and keep your audiences' attention rapt is to offset the audio and video edits to create a split edit.

This way, the audio is continuous while the picture is changing and the picture is continuous while the audio is changing, giving the viewers something to follow along with, even while the other component is changing.

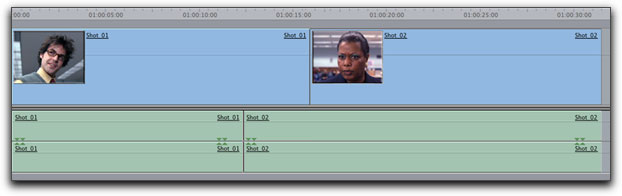

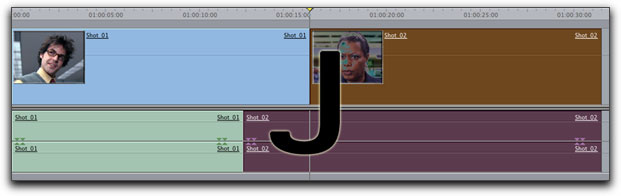

What, No K Edit?: There are two types of split edits, video leads audio and audio leads video.

Because of the way the tracks look on the timeline, these are commonly called L-cuts and J-cuts.

While splitting your edits in either direction does achieve the desired goal of maintaining some level of continuity across the edit point, in practice, I find that J-cuts are used vastly more often. This makes sense if you think of it like this: First the audience hears something new, and just as they wonder what caused that new sound, you provide the answer with the new visual information.

While split edits are most often thought of as a tool for editing dialogue scenes, I believe there are very few situations where you shouldn't at least explore whether splitting your edits might smooth out otherwise choppy edits.

Matching Angles

Another general rule that aids in hiding edits is to match shot types, CU to CU, MCU to MCU, and so on. One of the most important aspects is to match eyelines (at least if the two subjects are supposed to be looking at one another), but even when cross-cutting between two dissimilar scenes the smoothest edits will be ones where the overall composition of adjacent shots is similar or reciprocal.

A Match Made in Heaven: These two shots are perfect reciprocals of each other. Notice the exact same

amount of "shoulder" in the foreground of each, and perfectly matched eyeline. The camera crew probably

measured to make sure the camera was exactly the same distance from each of them and the same lens was used.

Furthermore you should strive to match similar or complementary lens choices whenever possible. Cutting between two shots where one is shot with a wide-angle lens and the other is shot with a telephoto lens (even if they're both MCUs) will be far more jarring to the viewer than matching shots photographed with the same lens.

Mismatched Shots: While technically both shots are CUs, one is shot with a longer lens and looser framing

and the other with a wide-angle lens and very tight framing. One is also dirty meaning that part of the other

player is visible in the foreground. Cutting from one to the other creates an unnatural juxtaposition that

threatens to pull the viewer out of the story.

Similarly, if one shot has been filmed at a high angle, the ideal reciprocal shot should be shot from a corresponding low angle. This is most obvious when the lens angle is motivated by the physical blocking of the actors (so the lens choices simulate the characters' points of view), but it applies equally when the use of low or high angles is done for subtle subjective reasons.

Don't Jump!: No jump cut is required here, since you've got two perfectly matching angles, one very low

angle, and one very high angle. The movement of character's arm gives a perfect cut point between them.

In addition to matching similar angles, it's also important to match moving shots to moving shots and static shots to static shots. If you need to cut from a pan to a lock-off, be sure to wait until the pan comes to its natural resting point, then cut to the static shot.

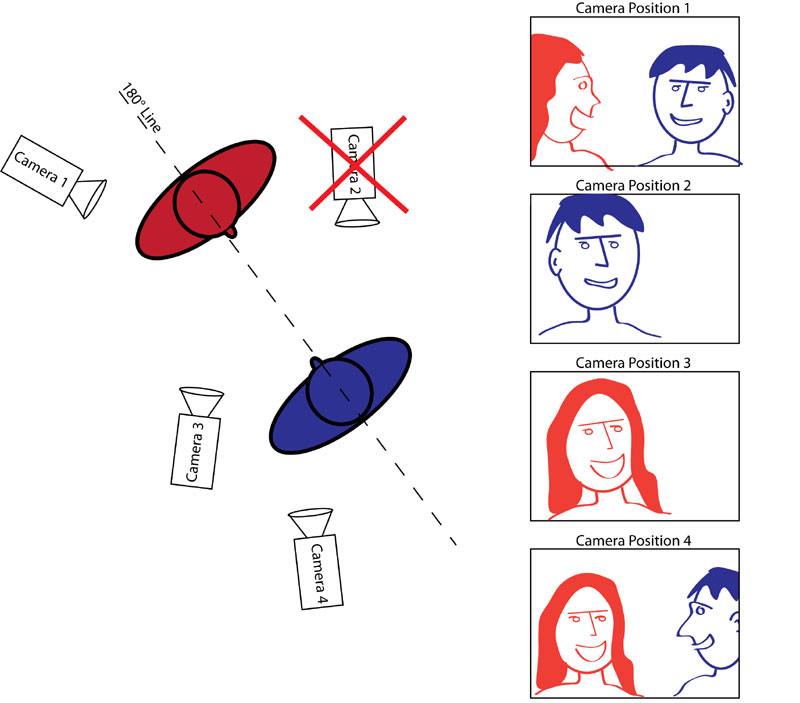

The 180° Rule

This is perhaps the most notorious filmmaking rule, and it's something that needs to be adhered to while shooting, but as an editor, you are often forced to try to fix or work around mistakes made when your production team failed to observe it.

The basic rule is that if people were looking left-to-right in the real space where the scene was shot, they ought to still be looking left-to-right in all of the shots when you edit them together. This might seem painfully obvious, but it turns out that when you convert the three-dimensional world into a series of two-dimensional images, it's pretty easy to get yourself turned around, and suddenly one of your actors is looking the wrong direction. While each individual shot might look fine, when you cut them together, that one shot won't cut properly with the shots around it. Sometimes the error is subtle and sometimes it's egregious.

The reason this is called the 180° rule is because you can move the camera angle away from a subject's eyeline by 10 degrees, 90 degrees, even 170 degrees, but if you move it beyond 180 degrees, suddenly the screen direction in the resulting shot will be reversed. The boundary can be easily assessed by imagining a straight line between the eyelines of the two main subjects.

Don't Cross the Line!: In the diagram above, you can see that the blue man is on the right side of the screen facing left in camera angles

1, 3 and 4, but in angle 2, he's on the left side of the frame, facing right. If you were to edit this shot into a sequence using the other three

shots, he would appear to be looking offscreen away from the red woman.

While this might seem simple, it quickly gets far more complicated when you have more than two people in a scene, or the people are moving around, or the camera is moving, or any combination of all these things. And God forbid if one of the shots is being filmed through a mirror! Even the most seasoned production crew can quickly get themselves very confused and accidentally move the camera to the wrong side of the line for part of a scene. And then, of course, it becomes your problem.

There are only a few ways to solve screen direction errors like this. The simplest is to apply a Flop filter to the offending shot, which will reverse the perspective.

A Safe Flop: Nothing in this shot gives away that it has been flopped.

However, this won't work so well if there's any text or a clock in the frame. Often just the relative position of the walls of the room can make a flop look worse than the original. Imagine a jail scene where suddenly one shot shows the felon outside of the bars!

Look Both Ways: While at first this might seem like a safe shot to flop, there's a dead giveaway...unless

the scene was suddenly transported from Los Angeles to London.

Fixing Screen Direction Errors Editorially

If you have a different shot where there is no discernable screen direction (the characters are looking straight at the camera) you can cut to that neutral shot, and then cross the line on the next cut. However, once you're on the other side of the line, you have to stay there, or re-use that neutral shot again to cross back over.

The only other practical solution to working around such screen direction errors is to find a shot where the lens moves across the line while the camera is rolling. Then, from that point forward you can use the footage shot from the other side. But again, you've got to stay there unless you have another shot where the camera crosses back to the first side.

Often you have no choice but to omit the bad shot, or in the worst-case scenario where the shot is absolutely essential and you can't cheat your way around the line, you just have to live with it. Chances are, most audiences won't immediately recognize what's wrong, but I can promise you that's exactly one of those moments where suddenly everyone in the theater is unconsciously shifting in their seats, looking down and realizing their out of popcorn. And you know what that means: they're out of the story too.

Mastering these concepts and rules will help you avoid common mistakes and quickly solve potential problems that frequently occur in the editing room. There are plenty more rules and guidelines that can improve your editing, though like all languages, this one is constantly evolving: Idioms get introduced, overused ideas become clichˇd and fall out of fashion, and smart and innovative storytellers will continue to invent new ways to communicate, and those will get copied and repeated and eventually will work their way into the mainstream.

The one rule that supercedes all the others is that if it works, it's right. And if it doesn't work, you need to go back to the editing room. If your test audiences (i.e. your wife and kids) don't understand what you're trying to communicate, try a different approach. Check that you're providing the answers to the six questions, and not dwelling too long on one or another. Storytelling is an ancient art, and one that when done right can stir our very souls. After all, that's why you got involved with this crazy medium to begin with, isn't it?

Michael Wohl is an award-winning filmmaker, instructor at UCLA, author of eight books on editing and storytelling using Final Cut Studio, and was one of the original designers of Final Cut Pro.

[Top]

copyright © www.kenstone.net 2008

are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Apple. Other company and product names may be trademarks of their respective owners.

All screen captures, images, and textual references are the property and trademark of their creators/owners/publishers.